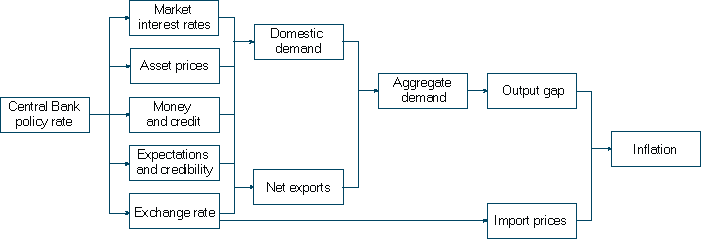

Monetary policy transmission

The principal policy instrument that the Central Bank uses to attain the inflation target is its interest rates on transactions with other financial institutions, which then affect other interest rates in Iceland. Commercial banks and pension funds generally change their interest rates after changes are made to the Central Bank’s key interest rate. If interest rates are raised, it becomes more costly to borrow funds and more beneficial to save. If interest rates are lowered, the reverse applies. In this way, monetary policy affects the saving and spending decisions made by households, businesses, and the public sector, which in turn affect the price level. If people spend less and save more, there is less incentive to raise prices, and vice versa. If the Central Bank considers it warranted, it can also conduct transactions in the interbank foreign exchange market so as to affect the exchange rate of the króna, thereby affecting the price level.

Show all

Interest rates

Credit channel

Exchange rate channel

Asset price channel

Expectations

Monetary policy transmission mechanism:

A more detailed discussion of monetary policy transmission can be found in Thórarinn G. Pétursson, “The transmission mechanism of monetary policy”, in Monetary Bulletin 2001/4, and in the Bank's QMM handbook: “QMM: A Quarterly Macroeconomic Model of the Icelandic Economy”, Ásgeir Daníelsson, Lúdvík Elíasson, Magnús F. Gudmundsson, Svava J. Haraldsdóttir, Lilja S. Kro, Thórarinn G. Pétursson, and Thorsteinn S. Sveinsson.